by Sukalp Muzumdar and Hanna Bobrovsky

(Disclaimer — The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the authors’ employers.)

A Deloitte report from last January (2023) pegged the cost of developing a new pharmaceutical asset in 2022 at $2.3 billion, and estimated that the average oncology trial takes about 11.6 years from the start of Phase I to the completion of Phase III — which is an enormous investment in both dollars and time for any player in the market, big or small. Coupled with a an absymally low success rate for clinical trials (while success rates for individual phases might be relatively high, cumulative success rates across phases were around 5% for oncology trials), and a general slowdown in pharma/biotech deal-making and M&A, it is evident that the current market situation is untenable for smaller companies seeking to bring new pharmaceuticals to the market.

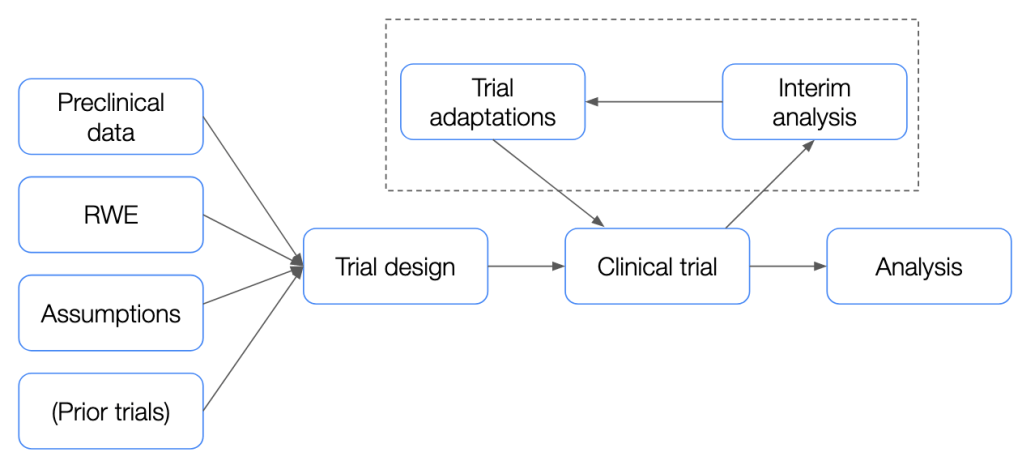

While there are a multitude of factors which drive these sky-high costs, one important area for improvement identified in the same report is a switch to flexible and adaptive trial designs which would enable quicker and more targeted course correction if the success of a clinical trial is deemed to be at risk.

What are some of the limitations associated with classical trial designs?

Building on in vitro and animal model data obtained in preclinical studies, the clinical development process typically consists of several clinical trial phases before a new drug is given marketing approval. The first of these, the Phase I trial is usually intended to measure safety and tolerability, the Phase II trial next is usually associated with an evaluation of dosing as well as preliminary efficacy, and the final pre-marketing, Phase III trials usually provide a concrete evaluation of drug efficacy relative to an active or placebo control. While this general testing pipeline has several possible modifications and variations, the overall process is relatively rigorous and has to clear several, high regulatory hurdles for a drug to make it to market.

This process is also heavily guided by several assumptions made during the planning phase which may or may not hold up in the recruited trial population. For instance, when performing sample size calculation for a clinical trial, assumptions are made about the effect size and the variability across the arms of the trial (e.g. mean progression-free survival in treated group relative to placebo for an oncology trial, standard deviation of the observed response etc.), which are typically based on either expert knowledge or observations from previous clinical trials. However, if the effect size is smaller in the trial population, or if the variability in the treated group is greater than expected, this can lead to trial failure due to the inability to successfully reach primary endpoints.

While of course this could be a function of the treatment itself, in some cases, incorrectly-made assumptions can also doom a trial to failure. For instance, we might observe that the drug appears to provide a significant benefit to a specific, small subgroup of the overall population which can be identified by a biomarker, while not demonstrating a large effect overall. In other instances, the observed effect of the investigational product may be smaller than expected, or the sample-level effect size variance higher than expected. In all these cases and more, standard clinical trials designs are limited in their ability to adapt to and address these unforeseen challenges. This is where adaptive trial designs come into play, offering a more flexible and dynamic approach.

Adaptive clinical trials come in many shapes and forms, but typically revolve around empowering researchers to leverage accumulating trial data to modify and optimize certain aspects of an ongoing clinical trial. Adaptive designs allow for modifications to the trial protocol based on interim results without undermining the validity and integrity of the study. This could include adjustments in sample size, dosing regimens, or even the inclusion of additional patient subgroups.

“A clinical trial design that offers pre-planned opportunities to use accumulating trial data to modify aspects of an ongoing trial while preserving the validity and integrity of that trial.” Definition of an adaptive clinical trial from the adaptive designs CONSORT extension (ACE) — guideline for reporting adaptive randomized trials (emphasis authors’)

Although the statistical analysis and modeling frameworks such as group sequential designs necessary to allow for the conduct of adaptive trials whilst ensuring statistical robustness were developed beginning in the 1970s, they have not found much favor until relatively recently.

Today, the FDA as well as the EMA have published comprehensive position papers wherein the intricacies of adaptive clinical trial conduct are dealt with in detail.

“By modernizing our approach to the design of clinical trials, we can make drug development more efficient and less costly while also increasing the amount of information we can learn about a new product’s safety and benefits. Using more modern approaches to clinical trials, we can lower the cost of developing new drugs and increase the amount of competition in the market” — FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D. while introducing the FDA guidance on adaptive clinical trials

In general, adaptations to a trial can be grouped into two broad categories — those based on a non-comparative analysis (where the blinding remains intact — i.e. treatment assignment is not considered in the interim analysis), and those based on a comparative analysis (which requires breaking the blind).

Non-comparative analyses are typically more limiting in the types of adaptations they enable — e.g. adjustment of sample size based on an estimation of blinded variance/effect size across groups, or limited changes to recruitment strategies, but if carefully and appropriately pre-specified in the trial protocol, typically do not result in an inflation of the type I error rate.

Comparative interim analyses on the other hand enable a wide range of adaptations to an ongoing clinical trial — be it sample size re-adjustment, or stopping for early efficacy/futility, or changes in recruitment strategies such as adaptive randomization or biomarker-driven recruitment, amongst many others.

With their inherent flexibility and dynamic nature, most adaptive trials, especially those with comparative interim analyses necessitate meticulous statistical considerations to ensure the integrity and validity of their results. Key amongst these considerations is the need to maintain the statistical power of the study while controlling for type I error rates in a robust manner, despite the potential changes being made to the trial design based on interim data analysis. This balancing act is crucial as any adjustments to the trial—be it in the form of sample size modifications, dose adjustments, or the inclusion of new patient subgroups—must not invalidate the trial’s findings. To achieve this, adaptive trials often employ specific statistical methods and metrics like group sequential designs, Bayesian adaptive randomization, and the predictive probability of success. These methodologies allow for the pre-planned, data-driven adjustments that characterize adaptive trials, ensuring that modifications are made in a statistically sound manner and also optimize for the likelihood of trial success. Trial adjustments at interim analysis are often based on a calculation of conditional power (or the Bayesian predictive probability of success which is able to guide decisions using trial-external information as well), which quantifies the likelihood of success, i.e. of achieving a statistically significant outcome given the current data at interim.

Typically, the statistical considerations involved in adaptive trial designs are complex, and thus simulation becomes an indispensable tool in the trial design and execution process. Simulation in the context of adaptive trial designs serves several critical functions. Firstly, it allows researchers and statisticians to explore the implications of various adaptation strategies before the trial begins, providing a sandbox in which the effects of adjusting sample sizes, endpoint definitions, or inclusion criteria can be easily assessed. This predictive modeling is invaluable for identifying potential pitfalls and optimizing the design for success. Secondly, simulation plays a crucial role in demonstrating to regulatory bodies that the proposed adaptive mechanisms will not compromise the trial’s integrity or the reliability of its results. Through extensive simulation studies, trial designers can justify their chosen adaptive strategies, showcasing how they plan to manage risks and ensure robust outcomes. This process not only aids in securing regulatory approval but also bolsters the confidence of stakeholders in the trial’s design and its ability to adapt to operational and technical issues necessitating adaptation.

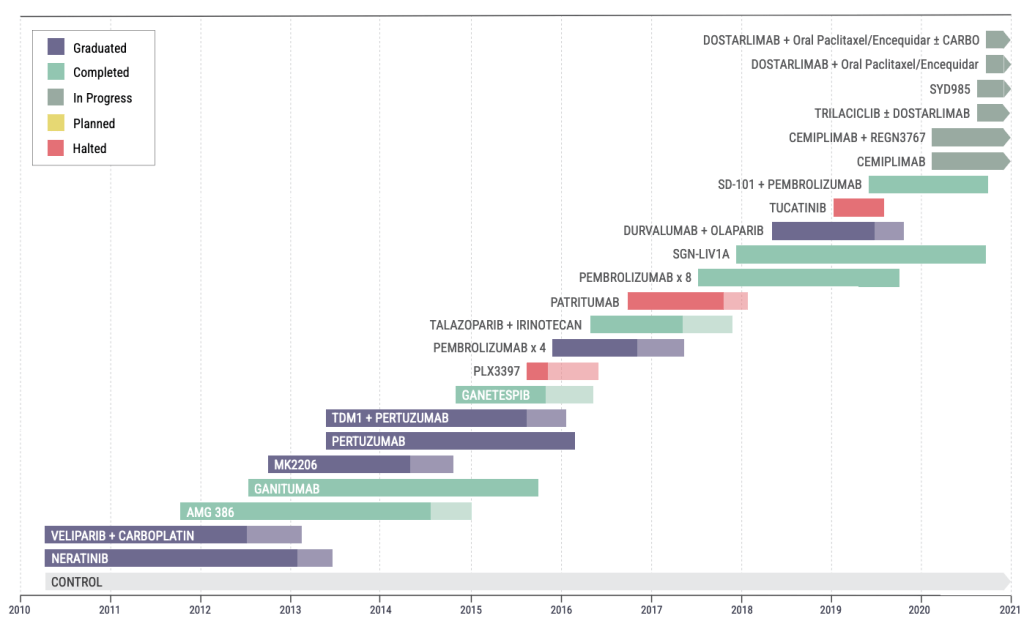

The I-SPY 2 (Investigation of Serial studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response with Imaging and Molecular Analysis 2) trial is an important example of a (still ongoing) breast cancer neoadjuvant adaptive platform trial. Biomarker profiling is performed on participants and tumors are classified into 1 of 10 subtypes, following which randomization is performed in an adaptive Bayesian manner, wherein arms are picked based on the probability of clinical response as indicated by accumulating trial data. Additionally, the trial allows for the introduction of new arms/drugs which have existing initial safety and initial efficacy data from a phase I trial, as well as for the dropping of arms which have not demonstrated efficacy for any molecular subtype(s). This adaptive design allows for the efficient and rapid evaluation of several drug combinations.

Another classic example of a biomarker-driven adaptive trial is the BATTLE trial, which used molecular profiling of lung cancer biopsies to adaptively randomize patients to a suitable treatment arm. While the study team retrospectively identified some limitations in the trial such as composite biomarker groups (sets of biomarkers) being less predictive than individual biomarkers, and some biomarkers having no to little predictive value, it is an important example of how clinical development is moving towards a personalized medicine paradigm.

The Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) is another example of a complex adaptive platform trial, which has so far recruited over 23,000 patients. The primary target population was patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with community-acquired pneumonia (i.e. not linked to a hospital stay), with the goal of evaluating the optimal set of treatments. While in usual clinical trials questions about different aspects of complex care as delivered in an ICU setting have to be evaluated separately or sequentially, the multifactorial nature of this trial enabled treatments across multiple “domains” (e.g. antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, corticosteroid regiments etc.) to be evaluated in parallel, thereby also allowing for investigators to consider important cross-domain interaction effects. Again, taking advantage of its adaptive design, accumulating trial data was leveraged for adaptive randomization, assigning patients to sets of treatments most likely to succeed with higher probability. This trial also played an important role in the evaluation of novel treatments in the recent COVID-19 pandemic, such as hydroxychloroquine, as well as Ivermectin.

Adaptive trials represent a great opportunity to all stakeholders in a clinical trial. From the trial sponsor’s perspective, they provide an agile framework which can significantly mitigate the financial risks associated with drug development. Traditional trial designs often fall short in accommodating the dynamic nature of clinical research, and are often behind costly delays or even trial failure when unforeseen challenges arise. Adaptive designs empower sponsors to make evidence-based adjustments such as adjustment of dose levels, modification of patient recruitment and randomization strategies, or even adjusting the sample size to de-risk the trial from incorrect initial assumptions. Additionally, the use of biomarker-driven trials also enables sponsors to target the appropriate population for a drug, thereby de-risking trials from efficacy-linked failures and enhancing the chances of regulatory approval.

From the patient perspective, adaptive trials can potentially significantly shorten the time-to-market for a new, efficacious drug. Additionally, for trial participants, the use of adaptive randomization or biomarker-driven randomization increases the likelihood of being assigned to more effective treatment arms as the study progresses, and furthermore, pick-the-winner/drop-the-loser strategies ensure that the risk-benefit ratio of such trials is enhanced compared to traditional designs.

Finally, from a regulatory perspective, adaptive trial designs allow for more efficient and informative regulatory review processes. For instance, a trial which allows early stopping for futility decreases the number of patients exposed to a treatment unlikely to demonstrate significant clinical benefit. Adaptive biomarker-driven enrichment strategies provide a more nuanced picture of drug efficacy and can drive more efficient trials down the road.

From an efficiency standpoint, Master Protocols as used in the I-SPY 2 and REMAP-CAP trials above represent an exciting novel step forward in clinical trial methodology and can have large effects on expediting clinical development and will be explored further in a future post here.

Nonetheless, adaptive trials come with their own unique set of challenges which are important to consider when planning such a trial. Firstly, adaptive trials are typically associated with complex statistical analytics procedures often requiring in-depth trial simulations, which can add a significant technical burden relative to traditional trials. Secondly, adaptive trials are also associated with an increased operational burden, including the logistics of implementing any changes mid-trial and ensuring that all stakeholders are aligned with these changes. Maintaining the integrity of blinding is another crucial aspect of running adaptive trials, for which it is important that access to interim analyses is strictly restricted. Nonetheless, even with restricted access, adaptations carried out in a trial have the risk of influencing investigators negatively – for instance an increase in sample size following interim analysis could be interpreted as the data pointing towards a smaller-than-expected effect size, which could have knock-on effects on recruitment and retention.

In conclusion, adaptive trials are an important tool in the clinical development arsenal, and are only recently being used to their full potential. The agility, efficiency, and flexibility afforded by these trial designs often offsets their drawbacks, which can be further mitigated by meticulous planning, rigorous statistical analysis, and transparent reporting.

References

- Deloitte pharma study: Drop-off in returns on R&D investments – sharp decline in peak sales per asset

- Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials of Drugs and Biologics — Guidance for Industry (FDA guidance)

- Reflection Paper on Methodological Issues in Confirmatory Clinical Trials Planned with an Adaptive Design (EMA guidance)

- FDA press release on Master Trial Protocols and Adaptive Trial Designs

- Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products — Guidance for Industry (FDA guidance on enrichment in trials)

- Adaptive designs in clinical trials: why use them, and how to run and report them

- The Adaptive designs CONSORT Extension (ACE) statement: a checklist with explanation and elaboration guideline for reporting randomised trials that use an adaptive design

- Group Sequential Methods in the Design and Analysis of Clinical Trials

- The I-SPY platform trial

- I-SPY 2: a Neoadjuvant Adaptive Clinical Trial Designed to Improve Outcomes in High-Risk Breast Cancer

- The BATTLE Trial: Personalizing Therapy for Lung Cancer

- Randomized Embedded, Multi-factorial, Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

- Master Protocols: Efficient Clinical Trial Design Strategies to Expedite Development of Oncology Drugs and Biologics Guidance for Industry

Leave a comment