by Sukalp Muzumdar and Hanna Bobrovsky

(Disclaimer — The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the authors’ employers.)

One of the overarching goals of statistics is to enable a principled analysis of data to come up with measures that help quantify the certainty or reliability of inferences drawn from that data.

Statistics plays a key role across diverse areas — be it in informing investors contemplating betting their money on a new product, or in guiding medical bodies towards adopting a new drug as the standard of care, or for banks determining the creditworthiness of debtors, and all the way up to guiding governmental decisions on education, monetary or military policy with important implications on everyday life.

Key then, to the statistical world is the ability to place a confidence measure on our ability to adjudge the probability of making a right/correct decision and how worthy an idea is of further pursuit. This is particularly important in biomedical and biotech research, from the early, pre-clinical stages of hypothesis generation, all the way to the later stages of clinical trials, where the stakes are high and mistakes may have a substantial human and economic cost. In these fields, the use of principled statistical analyses to determine the likelihood of correct decision-making — e.g., whether an investigational drug is effective, whether a genetic mutation is associated with a disease, or whether a new medical device is safe — becomes not just a methodological priority, but an ethical one as well. Furthermore, drawing conclusions from experiments without ensuring proper statistical rigor is an important contributing factor to today’s crisis of replication in biomedical research, a crisis which has been associated with billions in sunk costs.

Frequentist statistics hinges around the concept of hypothesis testing, wherein a null hypothesis of no change or difference is typically set up. After data collection, hypothesis testing is then carried out against an alternate hypothesis, which posits the presence of a change or difference. The outcome of this hypothesis testing is subject to two common errors — type I errors (false positives), wherein a true null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected, and type II errors (false negatives), wherein the statistician fails to reject a false null hypothesis. In frequentist statistics, α and β are conventionally used to represent the thresholds for type I and II errors respectively. The threshold for α is often set at 0.05, representing a commonly acceptable 5% probability of incorrectly rejecting a true null hypothesis, leading to a false positive result.

So far, so good — however what happens when multiple tests are carried out?

Opting for a standard α level of 0.05 implies that we are accepting that in 5% of cases, a more extreme result might have been obtained if the null hypothesis were true. Conversely, we are accepting that we would be able to correctly fail to reject the null hypothesis in 95% (1 — α) of cases across many trials. Nonetheless, the confidence in making several correct rejections drops exponentially when we are considering several tests — as laid out in the following:

Assuming the null hypothesis is true, if we choose a conventional α threshold of 0.05, by corollary, the probability (p) of not making a type I error is 1 —α = 0.95. Extending this over n hypothesis tests, we have

Probability of not making a type I error across n hypothesis tests

as the probability of correctly deciding to accept or reject every null hypothesis. Following from this, the probability of making at least one error comes out to

Probability of making at least one type I error across n hypothesis tests

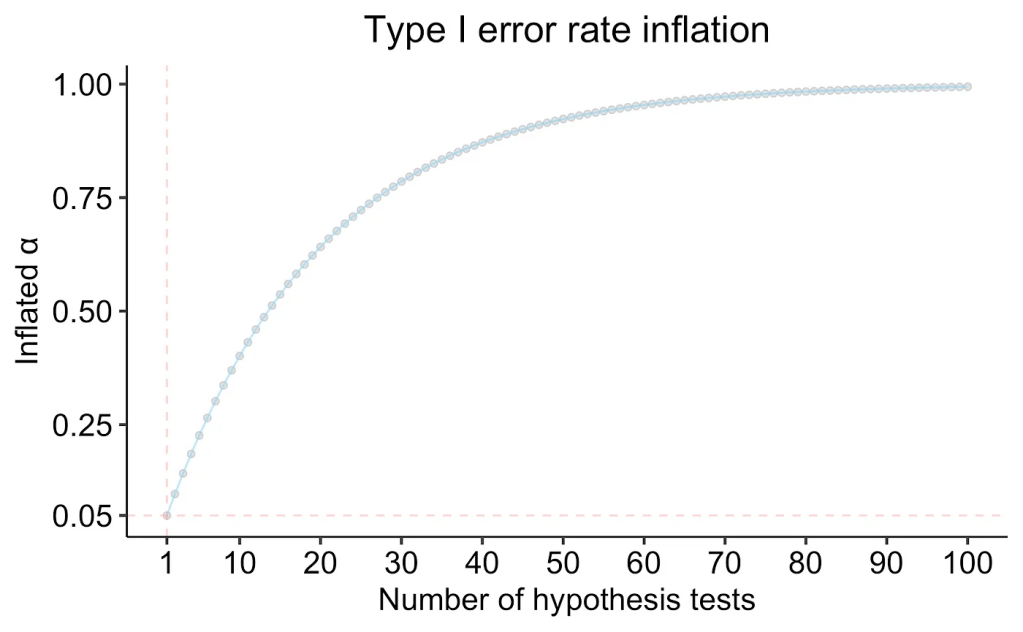

which can be represented as in the following plot (monotonically increasing and asymptotically approaching p=1).

If we were to conduct even just 5 independent hypothesis tests (a very reasonable number even in the context of clinical trial endpoints), this balloons our chance of making a type I error in at least one of the hypothesis tests to 22%. At 20 tests, this value is at 64%, which for most statisticians would constitute an unacceptably high probability of making a type I error.

Does this sound like an abstruse, constructed problem, which is of no real relevance to everyday science? Not really — ignoring these issues could lead researchers to believe that sufficient statistical evidence exists to justify very unlikely propositions, such as the classic examples of the dead salmon able to perceive human emotions in pictures, or that people born under the star sign of Leo are more prone to gastrointestinal hemorrhages — of course, these are constructed examples to demonstrate the importance of multiplicity correction.

Adjusting for multiple comparisons can be thought of more than a formal statistical technique; it is indeed a critical safeguard against the human tendency to find patterns in noise.

So how can this be overcome? In what contexts is it a problem? This is a question which has kept statisticians busy ever since the advent of Fisherian hypothesis testing. Some of the most frequent(ist)ly-used methods are detailed below. The Bonferroni method, first described in the 1930s, is one of the simplest methods for multiplicity correction, which simply divides the threshold for rejection by the number of tests performed within a family, ensuring that the “family-wise error rate” is effectively controlled.

Statisticians like to refer to the Bonferroni correction as a method of controlling the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), which in simple terms translates to the chance of even a single error being made in rejecting even one out of all null hypotheses being tested. While elegant in its simplicity and ease-of-use, the Bonferroni correction is frequently criticized as being very conservative, as it leads to a loss of power (by inflating the type II error rate β), however in some cases, where investigators are more concerned about false positives rather than false negatives, such strict control of the FWER is necessary. An example could be in a confirmatory clinical trial for a medicine which is expected to replace the currently existing standard of care — if efficacy is being measured across several equally important primary endpoints, a Bonferroni correction may be called for. Nonetheless, more powerful alternatives have been developed which allow for a more calibrated tradeoff between type I and II errors, such as the Holm-Bonferroni and Šidák procedures.

When conducting early-stage and exploratory research, we are typically okay with a few false positives slipping through, as the opportunity cost of missing an important discovery by severely reducing the power of a study is often much higher. This is typically the case in discovery and preclinical work, and in such cases, the Benjamini-Hochberg correction which controls the False Discovery (FDR) rate is often sufficiently stringent. This is often the multiplicity test of choice when working with high dimensional ‘omics data such as transcriptomics or proteomics data in exploratory settings where each feature is being tested for association with the outcome or condition under consideration.

What role does multiplicity correction play in regulated environments such as clinical trials?

When designing trials with multiple primary or even secondary endpoints, several important considerations have to be made with respect to multiplicity correction. Multiplicity issues (both obvious as well as not-so-obvious) can arise in several ways in clinical trials — be it through the selection of multiple primary endpoints, or multiple comparator arms, or repeated or interim analyses, or even unplanned subgroup analyses. Regulatory authorities such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) have both published guidance documents detailing how multiplicity can be dealt with in a prinicipled fashion. Multiplicity issues are also a key component of the ICH E9 guidance document on statistical considerations in clinical trials and play an important role in establishing Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

Specifically, both the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) state the multiple testing correction is important when individual endpoints generalize to a larger, disjoint hypothesis — i.e. if only one of many listed primary endpoints is required to be significant for a confirmatory claim, then there are several chances to reject the null, which have to be corrected for in a principled, statistically-valid manner. Nonetheless, in the case that multiple primary hypotheses are required to be simultaneously valid, or multiple endpoints are bundled into a single composite variable (although problematic for other reasons), there is typically no type I error rate inflation, and thus no requirement for multiple testing correction. With regards to how primary and secondary endpoints are treated, the FDA advocates for strict control of Type I error rate by treating both primary and secondary endpoint families as one group, in addition to restricting evaluation of secondary endpoints to cases only where an effect on the primary endpoint has been shown.

Establishing a pre-defined hierarchy of outcomes is yet another commonly used technique to overcome issues with multiplicity. Herein, endpoints are pre-sorted by investigators in a hierarchy, and tests which can inform future decision-making are only carried out until the first failed rejection of a null hypothesis. As soon we fail to reject a null hypothesis while going down the hierarchy, regardless of the subsequent p-values, all claims lower in the hierarchy cannot be said to have been validated. This is typically a good approach in the case when the expected hierarchy can be readily derived from affiliated data prior to trial initiation (i.e. there exists an obvious ordering of outcome importance given the biological properties of the drug).

The use of multiple arms in a clinical trial can also be associated with multiplicity, based on how the trial hypotheses are structured. While an oversimplification of the complexity involved — typically the same principles as for trial endpoints also apply for multiple arms — if all individual null hypotheses are required to be rejected at a pre-specified alpha level then there is no alpha inflation, and multiplicity correction is usually not required. However, if there are several routes to make a claim about drug efficacy, multiplicity concerns have to be addressed in a principled manner, including using pre-specified statistical plans and/or adjustments for multiple comparisons.

In clinical trials, interim analyses to take preliminary looks at the data are oftentimes planned, and are often even required by ethics boards to limit the number of patients who might be exposed to a futile or even dangerous treatment. On the other hand, they also play an important role when a treatment is exceptionally promising, where withholding it from a reference comparator group could be considered unethical in diseases with a relatively acute clinical course. Such interim analyses also form the basis of adaptive trial designs which are recently gaining popularity. However, interim analyses are yet another way in which multiplicity sneaks in to clinical trial analysis. How can we be confident that the results we see are not simply a fluke of the data collected until that time, which might be negated, or even reversed when we collect more data? While this risk of course can never be entirely excluded, there are principled methods to ensure control of the risk of type I errors based on several looks at sequentially-collected data, which are best known as alpha-spending functions. Alpha-spending functions enable similar outcomes as other multiplicity correction methods — i.e. the control of type I error rates through an alpha adjustment for individual hypothesis tests. The most common of these are the O’Brien-Fleming, Lan-DeMets, and Pocock alpha spending functions. The primary idea behind alpha-spending functions is the allocation of an appropriate alpha for each look — early looks at the data may be typically associated with a significantly lower alpha — thus any decisions made at this early stage have a significantly higher threshold to clear to reject the null hypothesis, requiring stronger evidence to ensure the overall type I error rate is controlled across all looks at the data.

An important consideration to prevent issues of hidden multiplicity through additional, unplanned analyses in clinical trials, is the pre-registration of a trial protocol with the journal where the results are anticipated to be published, and following the CONSORT guidelines when preparing clinical trial-related publications. This ensures an effective blockade on the practice of (re-)defining trial endpoints post hoc, which is associated with several concerns about data dredging and p-hacking.

Multiplicity correction thus plays a crucial role in ensuring the validity of clinical trial results and promoting the dissemination of reproducible results.

Of course, to present a measured argument — it is important to consider both sides of the debate, and consider the flaws in multiple hypothesis testing correction, and whether there are any situations where it be done away with. Rothman in his 1990 article presents a passionate diatribe against the use of multiplicity correction in all except some “contrived settings”. The underlying argument is that the universal null hypothesis which is implied by chance is not an accurate model of how the real world works, with its high level of interconnectedness and correlations across variables and outcomes — and that scientists should not shy away from exploring results simply because they might have occurred by chance.

In conclusion, multiple testing correction could be thought of as a “necessary evil” — necessary to ensure the validity and reliability of inferences, which is especially important in high-stakes biomedical research, while at the same time, requiring scientists to walk a tightrope with regards to balancing type I (false positive) and type II (false negative) error rates. Bayesian methods offer another way out of these concerns, and are increasingly becoming an important part of the clinical trial world as well, although typically associated with increased statistical complexity.

References

- Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: the multiple problems of multiplicity — whether and how to correct for many statistical tests

- Neural Correlates of Interspecies Perspective Taking in the Post-Mortem Atlantic Salmon : An Argument For Proper Multiple Comparisons Correction

- Testing multiple statistical hypotheses resulted in spurious associations: a study of astrological signs and health

- FDA — Multiple Endpoints in Clinical Trials Guidance for Industry

- EMA — Points to consider on multiplicity issues in clinical trials

- No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons

- CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials

Leave a comment